In January 2014 Transport Canada released the report of just such an accident, in which the First Officer had "monitored" and repeatedly warned his Captain about what he believed to be an increasingly dangerous situation. Nevertheless the B737 was destroyed and most of those aboard were killed.

In January 2014 Transport Canada released the report of just such an accident, in which the First Officer had "monitored" and repeatedly warned his Captain about what he believed to be an increasingly dangerous situation. Nevertheless the B737 was destroyed and most of those aboard were killed.

In 2010 an Airbus A321 was destroyed and 152 persons died despite numerous warnings from the First Officer to the Captain that his chosen flight profile was dangerous.

In 2010 158 persons died when the Captain of a B737 continued an unstabilised approach despite repeated warnings and Go-Around calls from the First Officer.

In 2007 21 persons died and a B737 was destroyed when despite warnings from the First Officer, the Captain continued an unstabilised approach into a runway over-run.

In 2002 a B737 was destroyed during a non-precision approach when the Captain's negative attitude to his inexperienced First Officer had inhibited him from effective monitoring.

These are just a small sample from hundreds of "monitoring failures" that have proven lethal to passengers and crew over many decades. Other serious but fortunately non-catastrophic events have included near or actual loss of control, and Controlled Flight Towards Terrain events.

Cockpit Voice Recorders in many accidents and incidents have also documented events where the Pilot Monitoring has been aware of flight parameters that were incorrect, but rather than calling for a correction, has shared the Pilot Flying's apparent lack of concern, agreed with the PF's mental model of the situation or simply not wanted to interfere.

Examples include an event where an A319 First Officer was aware that the aircraft's trajectory was hazardous long before the GPWS "Pull Up" alert saved the day, but did not act because "having been a Captain himself, he did not want to encroach on (the Captain's) decisions".

In the majority of cases, the pilot monitoring has been the First Officer. In 1994, the US NTSB had noted this fact in its study of 37 accidents in the USA, and recommended action to address the situation primarily via more effective Crew Resource Management (CRM) training.

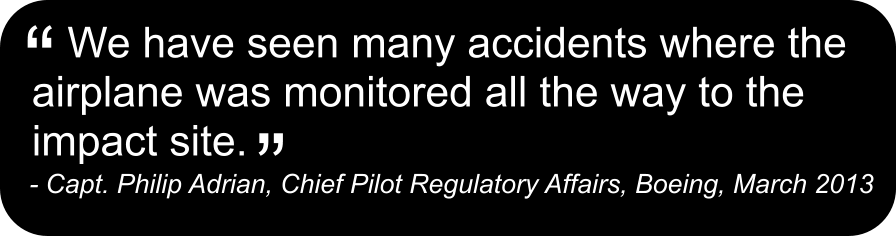

But even after years of CRM and other training, it is clear that when considered as the "overall aircraft control system" that they actually make up, the typical airline crew is still just not reliable enough. The way a typical crew works contains a "design flaw" that would never be tolerated in any aspect of physical aircraft systems. As the speaker quoted above went on to say, "Just monitoring is not sufficient!!! We need to create a link between the monitoring task and the actions that result from it."

In aviation there is a huge amount of discussion of monitoring, especially of automated aircraft systems, as an essential component of flight safety. The industry puts great store by achieving adherence to SOPs. But little actual effort has been made to embed the most effective cross-crew "monitoring" techniques as a key aspect of the most basic SOP for a two-pilot crew.

"Monitoring" that detects an error but does not result in change of aircraft trajectory or configuration is as useless as no monitoring at all.