The term "culture" has sometimes been used as a reason for poor pilot performance in monitoring. "Culture" or "how we do things in our group" is often used in over-general terms, when it actually has many complex aspects. Some cultural factors, particularly natural deference to authority in some cultures when viewed at the national level, is one, but only one, of the factors in the ineffective monitoring/CCAG issue.

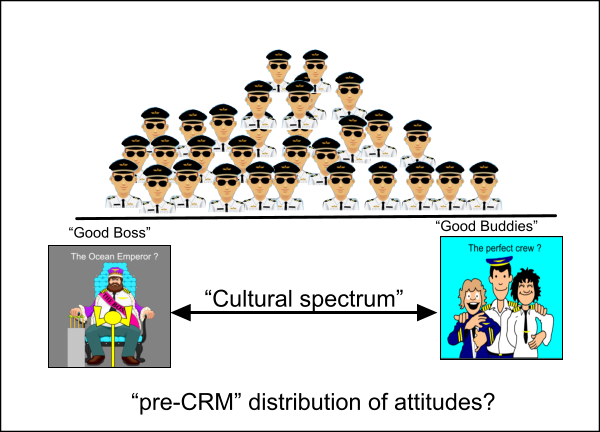

Culture, and particularly PILOT culture, is discussed in more detail in a separate section, but it is worth making one general point about it here. Because national cultures are only one factor in each airline's own culture, and there are so many possibilities, one might perhaps imagine any airline's pilots will fall somewhere on a spectrum between two generic extreme attitudes, caricatured here as "Good Buddies" and "Good Boss" cultures.

Good buddies and good bosses

"Good Buddies" is an ideal crew member concept to which CRM training seems to aspire. It is based primarily on strong respect for the individual, a cultural aspect in which Americans tend to be very strong. Its characteristics include emphasising that

- all individuals are equally valuable;

- teamwork needs a leader to be "first amongst equals";

- people should take turns to demonstrate their skills;

- there must be full respect for the inputs of all members of the team, regardless of their status.

In the ideal world of this concept, a flight crew would consist of experienced people who can respect and relate to each other as equals, taking it in turns to assist each other. Individual satisfaction is critically important. Expertise in piloting, being "a good stick" – i.e. control manipulation - is viewed as the most satisfying attainment, and the best collective result is obtained as a consequence of all individuals being satisfied. But as leading CRM expert Frank Tullo says "This individualism makes the formation of a good error detecting team all the more difficult to create."

At the other extreme is a "Good Boss" culture, which in some ways appeals not only to some national cultures but also to pilots who hark back to the good old days when "the Captain's authority was undisputed". Many societies have an ideal which is different to the "Good Buddies" concept. Its characteristics might include the view that

- high rank and authority inherently endow opinions and actions with correctness;

- high rank and authority inherently endow opinions and actions with correctness;

- the views of the most skilled and experienced team member should be the most respected;

- good teamwork needs a strong, decisive leader;

- the value of inputs is proportional to the importance of the team member.

Being an expert pilot is viewed as the most prestigious attainment. In this culture, the ideal crew would have a highly skilled commander, setting out a detailed and comprehensive set of rules for safe operation, accurately supported by qualified and obedient subordinates.

Group satisfaction is critically important, and an individual is satisfied best as a consequence of the group being satisfied – as opposed to the "Good Buddies" model, where group satisfaction is the result of each individual being satisfied. In these societies, respect for authority and conformity to group norms is seen as a very positive and beneficial thing. But in this culture, an unsatisfactory leader will cause his followers to pay a heavy price.

Changing "Good Boss" to "Good Buddies".

Although these are highly simplistic caricatures of pilot cultures, it is not unreasonable to assert that the natural distribution of the world pilot population would put with most pilots somewhere between the two extremes.

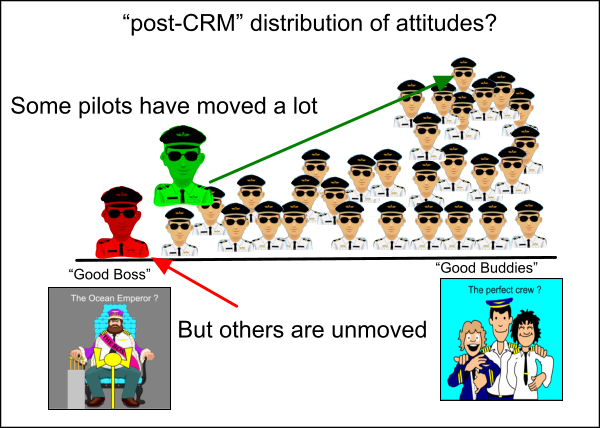

CRM training originated in the USA, and much of its focus has been the attitude, behaviour and performance of individual pilots. In particular, it has tended to imply that "Good Bosses" have little merit and should become "Good Buddies". But the continuing appearance of accidents in which poor CRM has been a major factor seems to indicate it is still an uphill task.

A

Flight Safety Foundation article in 2012 focused on the continuing problems of "Toxic Captains" who seem impervious to CRM training, and who are not limited to any particular culture. Bob Helmreich and others have noted that CRM training can "wear off" and needs constant reinforcement. A small but significant percentage of pilots reject CRM training, and some crews observed in line operations following initial CRM seminars do not practice the concepts espoused in training. Frank Tullo particularly notes the problem of getting good teamwork operating in an individualistic environment like the USA.

At the other extreme, Bob Helmreich recalls making a CRM presentation via a translator to senior managers and chief pilots in an airline in a culture of high respect for rank and authority. Stressing the importance of the first officer speaking up when the situation is deteriorating, he later learned that a senior manager had announced to all present that they should disregard everything he said.

The reality of CRM training.

Most countries now require CRM training at least for air transport operations, to meet the intentions of accident investigators recommendations and similarly motivated state regulatory organisations. Regulations say that operators should ensure that for example "all pilots have training in team management, communications, situation awareness, decision-making, and recognition of the resources available to assist the crew in the safe, efficient completion of any flight operations activities".

But accident investigations continue to reveal a startling discrepancy between good intentions and actual practice. In one recent accident to an airline that met that wording, the Captain had passed a recent proficiency check, although "graded at minimum standard at CRM/Threat & Error management and workload management". The F/O had met minimum standards and was also assessed "satisfactory". Nevertheless the F/O was unable to provide effective monitoring due to the excessive CCAG.

In another recent accident report, it emerged that the basic CRM training actually given to the F/O was limited to a total of 3 hours 10 min of potential tuition time in a classroom. When a similar course was observed, 5 of 8 mandatory topics were omitted. In fact this F/O's basic CRM training was essentially one half of a day which also featured briefings on the company's Safety Management System, and on various of its security requirements. Again, the F/O was unable to provide effective monitoring due to the excessive CCAG.

Unfortunately, telling people that they must change their entire social and cultural framework as well as their personal attitudes when they enter the cockpit is not going to be well received by a huge percentage of the pilot population.

This is inevitably going to be even more so when the message is conveyed by presentations in a language the pilot may not speak fluently. If the training is being outsourced by a start-up company employing pilots from many different nationalities, looking to fulfil its regulatory obligations at minimum cost, then it is hardly surprising that accidents where "poor CRM" is a factor continue to occur.

Clearly, given the realities, improving the effectiveness of cross-cockpit monitoring by attempting to achieve an universal optimised authority gradient is an uphill task with a very steep gradient of its own. And the industry cannot afford to wait decades for an improvement.

- high rank and authority inherently endow opinions and actions with correctness;

- high rank and authority inherently endow opinions and actions with correctness;